In less than a week, Britain will hold its third general election since 2015 and the welfare state, national security and even Scottish independence are all high on the agenda.

But disagreements over Britain’s departure from the E.U. are looming largest over the campaign. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party has promised in its official campaign slogan to “Get Brexit Done” if it wins, playing off widespread frustrations among people who voted to leave the E.U. in 2016 that, three and a half years on, Britain has still not left the European Union.

But that effort is facing a challenge from Jeremy Corbyn’s opposition Labour Party, which is promising a raft of transformational, progressive policies like pouring money into public services, nationalizing railways, providing all homes with free broadband, and investing in a “green industrial revolution” — as well as holding a second referendum on Brexit.

With Brexit now scheduled to happen by the end of January, the winner will have the responsibility to deliver it, reshape it, delay it, or cancel it altogether.

Here’s what to know about the U.K.’s upcoming election.

When is the election?

The election will be held on Thursday, Dec. 12.

It’s Britain’s first December election since 1923. Elections are normally held in May or June, when the days are longer and the weather is better. But polling experts are playing down the effect the winter will have on people voting: after all, both right and left are saying this election is the most important for a generation.

Why is there an election happening now?

Elections in Britain are meant to happen once every five years, but next Thursday’s will be the third since 2015.

Johnson, who leads a minority government, called for a snap election because lawmakers refused to ratify his Brexit legislation in October. Enough lawmakers then agreed that the impasse could only be solved by holding an early vote.

It follows the snap vote called by Prime Minister Theresa May in 2017, in which she sought a bigger mandate to deliver Brexit but ended up losing her majority.

How does a U.K. election work?

Britain is a parliamentary democracy, meaning that, unlike in the U.S., voters don’t directly elect the leader of the country. Instead, Brits elect Members of Parliament (MPs), at the constituency level. Those MPs belong to parties. The party that holds a majority of seats after the election is considered the winner, and its leader becomes Prime Minister.

If no party has a majority after the election, then the one with the largest share of the vote usually holds coalition talks to see whether they can reach a majority by teaming up with another party. Legislation can only pass the House of Commons with support from a majority of lawmakers.

Who’s running?

There are several parties running in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, but the five main players are the right-wing Conservatives or “Tories”, left-wing Labour, the centrist Liberal Democrats or “Lib Dems”, the single-issue Brexit Party and, in Scotland, the Scottish National Party or SNP, which wants Scottish independence.

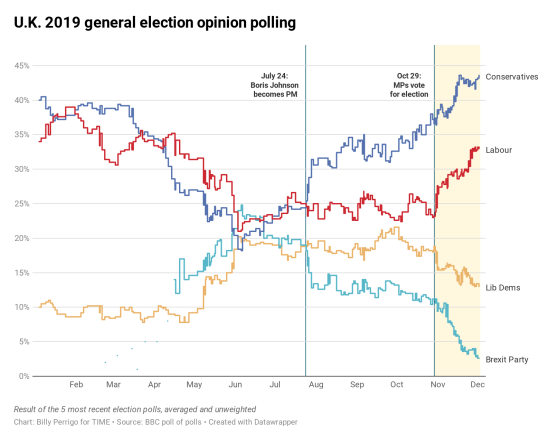

In the summer of 2019, before the election was called, it looked like Britain’s traditional two-party system was dead. The dominance of the Conservatives and Labour appeared eroded by Brexit, and the Lib Dems and newly-founded Brexit Party had risen in the polls, leaving all four parties polling at around 20%.

But public support for the Tories has more than doubled since June, after the party replaced Prime Minister May with Johnson. Labour’s support has risen since then too, largely at the expense of the Liberal Democrats, who had temporarily attracted some remain-leaning Labour voters by promising to cancel Brexit altogether, but whose support has steadily declined during campaigning.

How will the election affect Brexit?

If Boris Johnson gets a majority, he has promised that Brexit will happen in January 2020.

If Labour win, they have promised to renegotiate Johnson’s “hard” Brexit deal to something “softer,” resulting in a closer trading and regulatory relationship between the U.K. and the E.U. Labour have also promised to hold a second Brexit referendum after that renegotiation, where leaving and remaining in the E.U. are on the ballot. Corbyn has not said which side he would support in that referendum.

If no party wins a majority, which is still possible, there is a chance the election could change very little — especially if the new contingent of lawmakers are as divided on the issue of Brexit as the last one was.

What are the big issues in the election?

The election was called because of Brexit, but a terror attack at London Bridge and arguments over the future of Britain’s publicly funded National Health Service (NHS), along with other public services, have also received significant airtime.

Terror attack

On Nov. 29, a convicted terrorist who had been released from prison stabbed two people and injured three others before being shot dead by armed officers.

The stabbing had echoes of the June 3, 2017, terror attack at the same location, which came days before the last election. In the wake of that attack, then-Prime Minister Theresa May was criticized by Labour for her austerity policies that had reduced the number of police on the streets — and she subsequently lost her majority when voters went to the polls.

Keen to avoid a similar outcome, Johnson went on the offensive shortly after the attacks, blaming Labour for the terrorist’s early release—ignoring that it had happened under a Conservative government—and calling for tougher sentences for terrorists. His language dominated headlines in the right-leaning tabloid newspapers, but drew criticism from others, including victim Jack Merritt’s family, who called for their son’s death not to be exploited for political gain.

After a weekend of media appearances by Johnson and cabinet members attacking Labour on the issue, Merritt’s father published an article in which he said his son “would be seething at his death, and his life, being used to perpetuate an agenda of hate that he gave his everything fighting against.”

The attack dominated headlines for several days, but was bumped off the news agenda by Trump’s visit for the NATO summit without having much of a visible impact on the Conservatives’ lead in opinion polls.

National Health Service (NHS)

The Labour Party have capitalized on Trump’s previous comments indicating that Britain’s beloved NHS, which is publicly funded and provides free-to-access healthcare to anyone in the country, could be bought up by U.S. pharmaceutical firms after Brexit.

“When you’re dealing in trade everything is on the table, so NHS or anything else… everything will be on the table, absolutely,” Trump told reporters at a press conference in London in June.

Trump has since said his administration has no interest in the NHS, but the Labour Party is still raising the alarm about the prospect. “With a No Deal Brexit, your family’s medicine costs could skyrocket to unaffordable USA prices once Boris Johnson strikes a trade deal with Donald Trump,” says one Labour Facebook advert.

Labour insiders tell TIME that, while they are struggling to cut through to voters on Brexit, internal polling shows that their emphasis on the NHS and Johnson’s links to Trump has had an effect.

Trump’s visit

When President Trump was asked by reporters about the upcoming British election while visiting London on Tuesday, he was on his best behavior. “I don’t want to complicate it,” he said. “I’ll stay out of the election.”

It was a change of tack from just six months ago when, on his previous visit to the U.K., he had waded into British politics, criticizing then-Prime Minister May’s approach to Brexit negotiations and landing her in hot water electorally by saying Britain’s beloved National Health Service could be up for grabs in a post-Brexit U.S.-U.K. trade deal.

But May has since been replaced by Johnson, with whom Trump says he has a personal rapport. “We have a really good man who’s going to be the prime minister of the U.K. now,” Trump said when Johnson was appointed Prime Minister. “They call him Britain Trump, and that’s a good thing. They like me over there.”

The only problem for Johnson is that Brits actually don’t like Trump much at all. U.S. officials know that, and briefed the President to steer clear of British politics. In multiple press conferences across two days in London, Trump succeeded in not saying much that would damage Johnson’s chances.

For the most part, that is. Speaking at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence on Tuesday, Trump didn’t manage to stay away completely. “I think Boris is very capable,” he said, “and he will do a good job.”

Overall, however, when the wheels of Air Force One lifted off from the tarmac at London’s Stansted Airport late Wednesday, Johnson’s Conservative Party officials breathed a sigh of relief. They had acknowledged the Presidential visit would be a wildcard in an election campaign that had so far been kind to them. With just a week to go until Brits go to the polls, the Conservatives have a roughly 10 point lead and pollsters say they are on course to win a majority.